Rezarta, her mother, when asked how she feels about her dual national identity, shares that she went through a crisis when her citizenship application was rejected due to income criteria. “I cried uncontrollably as if I had lost someone. I thought to myself, I have done so much for Greece.” However, over time, she came to a different realization. “Everything I did here, I would have done anywhere. Did I do it for Greece? No, I did it for myself.”

Ioanna explains that, while she identifies as Greek because she grew up in the country, “it has to be clear that I am from Albania. I feel the need to say it because I never felt embraced by Greece as a state.” Anita expresses similar sentiments. “I always tried to convince myself that I feel Greek, but when I think about what my parents experienced, it pushed me away. I feel the need to hold onto my Albanian identity because, deep inside, I feel a sense of resistance.”

In contrast, her mother, Laureta, says she has Greece “in her heart.” “This is the country I feel is mine,” she says while never diminishing her Albanian identity. Endira feels similarly: “It feels like this is our homeland.” Her son, Bruno, shares that he feels equally Greek and Albanian. “I grew up here. I learned Greek culture, but still, I have a country that I cannot forget.”

On the other hand, Lia, Angela’s mother, feels “foreign both in Greece and Albania. In Albania, they say, ‘Here comes the Greek woman.’ In Greece, they say, ‘Oh, the Albanian.’ I’m not sure about my identity. It’s as if I no longer have one.”

Angela, however, feels that she doesn’t fully understand her dual identity. Though she acknowledges her origins, it doesn’t feel entirely clear to her. “The cultures are similar, so I don’t distinguish them so strongly,” she explains. Nevertheless, she says, “I don’t feel like my generation will focus on someone’s origin anymore, at least not in my circle.” However, she recognizes the role her parents played in this. “Maybe my parents made me not realize that I’m different,” she says.

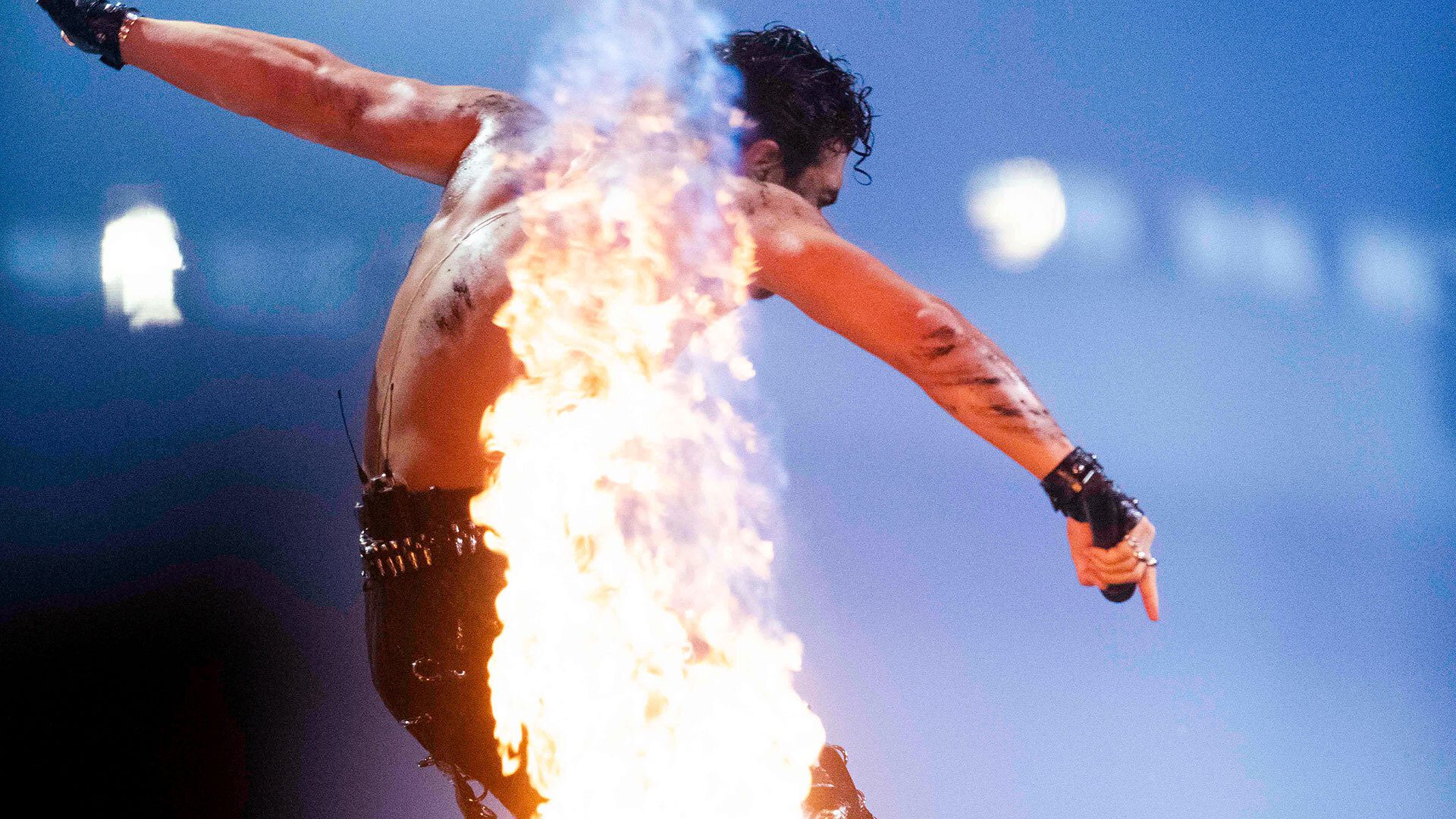

*All photos are courtesy of the interviewees.

What is fyi.news?

What is fyi.news?